Aikido Association of America home page. AAA's dojos are listed here; I hope you can find one near you.If not, AikiWeb maintains a wider directory of aikido schools, or simply Google "aikido <name of your city>."

Superb content at Aikido Journal. And great stuff (including my own posts) at the Aikido at the Leading Edge Facebook group.

The Conscious Manager's Reader Dialog Page includes questions and answers about aikido practice.

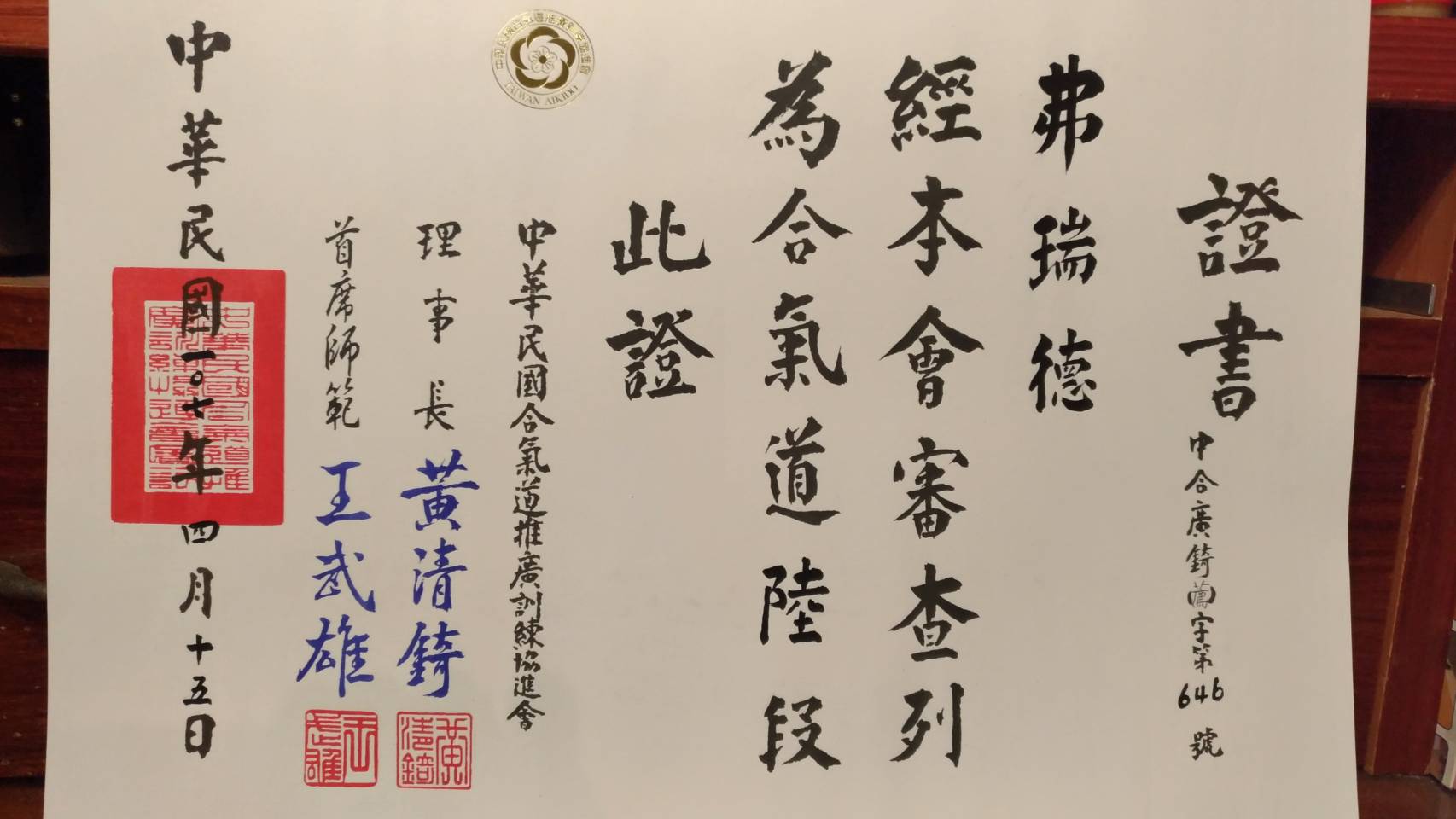

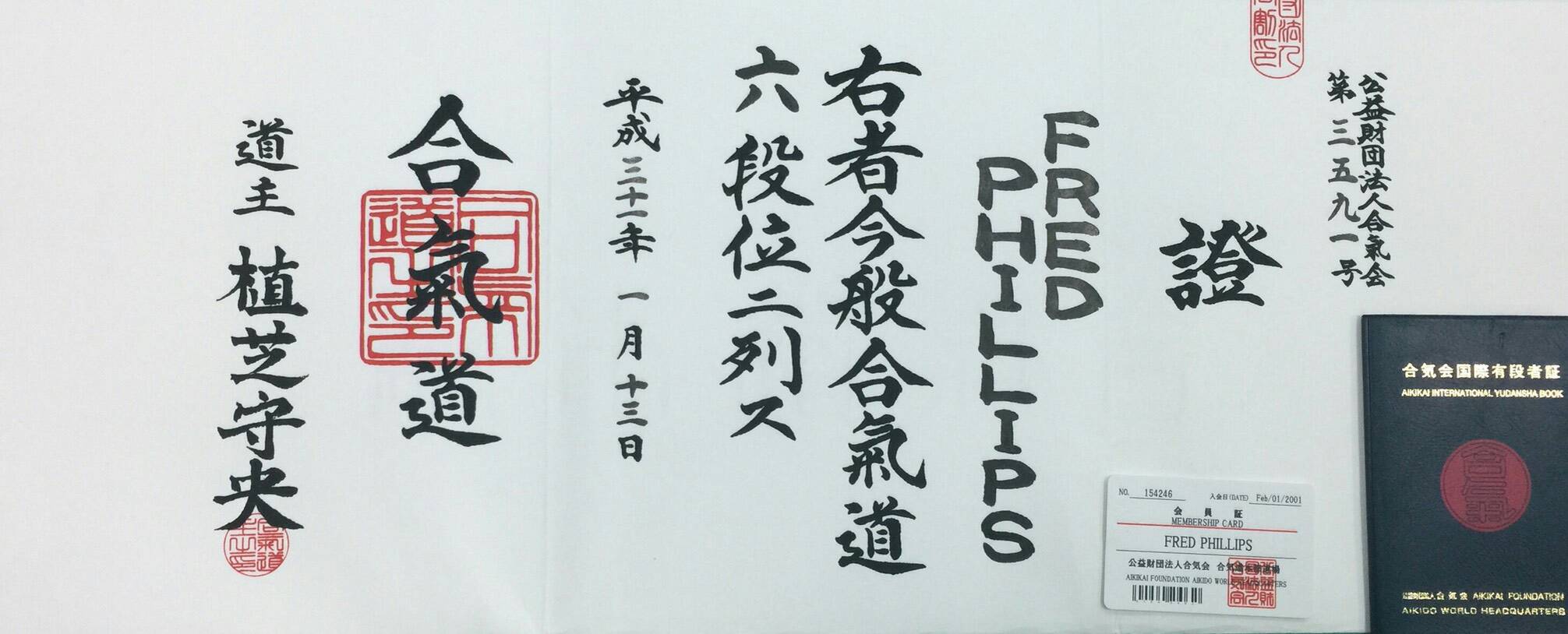

Fred Phillips, 6th Dan,

began his aikido training in early 1973. After breaking

too many bones (his own, not other people’s) during his year on

the 1972 University of Texas judo team, Fred wandered into Bill

Lee and Jay Portnow’s aikido practice. (Bill and Jay were,

respectively, students of Rod Kobayashi and Mitsunari Kanai.)

After one class, Fred knew he would practice aikido the rest of

his life.

When Fred won a

graduate fellowship for research in Japan, he trained under

Koichi Tohei Sensei at Ki Society HQ in Tokyo in 1975-76.

In 1977, Kobayashi Sensei awarded Fred shodan, and recommended

that he study with Fumio

Toyoda Shihan in Chicago.

In the next decades,

Fred ran dojos in Texas and Oregon under Toyoda Sensei’s

supervision. Shortly before he passed away in 2001, Toyoda

Sensei advanced Fred to 5th Dan, re-aligned Aikido Association

of America with World Aikikai

Honbu, and registered his students’ ranks with World

Aikikai Honbu.

In 2004, Fred moved to

Europe and enjoyed the hospitality of Aikido Tendo in Maastricht (the

Netherlands). His European job took him to Peru, Malta,

Cyprus, Belgium, Egypt, and Vietnam. In every country, he

practiced with, or was invited to teach at, local aikido

schools.

Between foreign

postings, Fred lived in San Diego, California, training

occasionally at the dojos of old friends Martin Katz and Ken MacBeth and

trying to learn Argentine tango at El Mundo del Tango.

From 2012 to 2015, Fred

worked in Korea, training and teaching with the World Aikikai

Honbu-affiliated Korean Aikido

Federation. In 2015 he was appointed Distinguished

Professor of Management at Yuan

Ze University in Taiwan, where he practiced and coached at

Dong Wu Dojo and at the National Chengchi University and

National Taiwan Normal University Aikido Clubs. He continues to

travel as guest and guest instructor at dojos worldwide.

Toyoda Shihan

Toyoda ShihanThis photo of Morihei Ueshiba O-Sensei, or one like it, appears

in every aikido school. He is the revered founder of aikido.

Koichi Tohei Sensei kindly responds to earnest questions from my

father and me, in Chicago, 1975. I later studied under

Tohei Sensei in Tokyo. Back to top.

Tohei Sensei at a public demonstration in Shinjuku, Japan,

New Year 1976. He is showing that it is easy to teach a child to

exercise the power of ki. (Photo by author.)

Senseis Bill Lee and Jon Takagi in front of my parents' house in

Illinois, 1975. Back to top.

The late Jon Takagi's little adobe dojo in downtown Phoenix. (Photo by the author.)

Rod Kobayashi Sensei, Armando Flores and Wynn Lee at the

University of Texas. Austin, probably 1976. (Photo

by the author.)

Hawai'i-born Roderick Kobayashi went to Japan for his education

and was not able to leave Japan until after World War II. He

trained under K. Tohei, and

later settled in California. Back to top.

A walking ad for the Austin Aikido Club, c.1976. Who could

resist? Hyonsook and I have been married since '79. (Photo by the

author.) Back to top.

Some stalwarts of the Ki No Kenkyukai headquarters dojo in

Haramachi, Tokyo, 1976. Back to top.

Aikijutsu class under the geodesic at Aspen Academy of

Martial Art, 1977. (Photo by the author.)

Yours truly performing jiujinage, around 1988. The

courageous uke is Dan Rabinovitsj. (Photo by Margaret

Schell.) Back to top.

Several of Jinshinkan Dojo's faithful core (L to R): Sergey

Zaderey, Don Neuhengen, Andrea Pavlick, Robert Rios, Scott Prahl,

Fred Phillips, Alex Nelson, Alex Kotov. At the Cornelius Pass

Roadhouse, Hillsboro, Oregon, 1999.

Teaching in Malta, 2005.

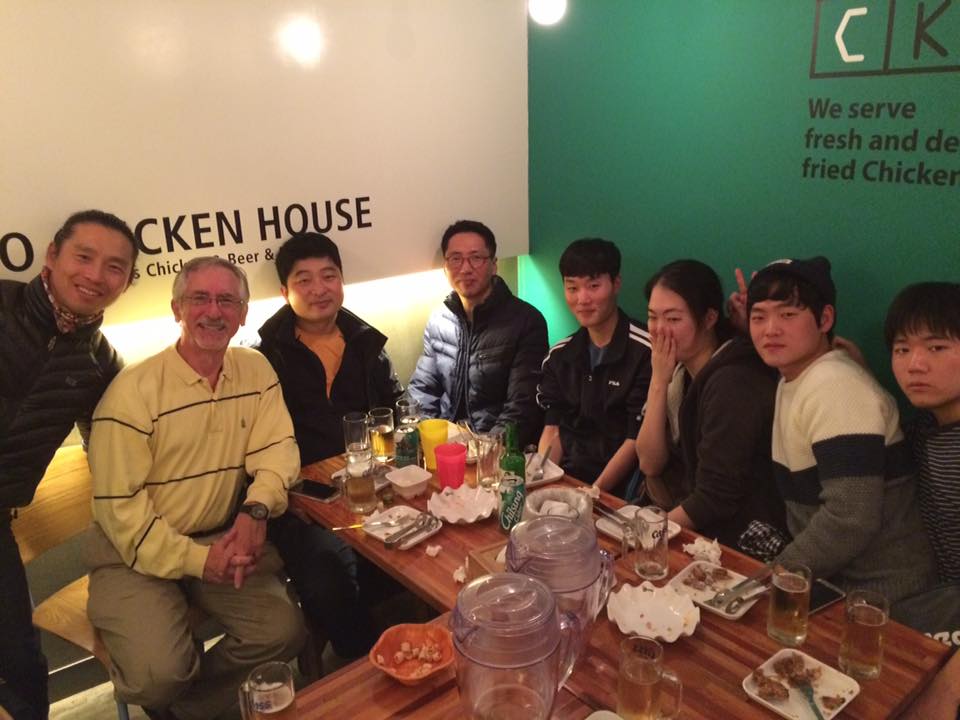

Left: Korean Aikido Federation HQ, Seoul, with Yun

Sensei, head of KAF.

Right: Members of the Incheon Dojo of the Korean Aikido

Federation. Dojo-cho Mr. Im, on my right.

Teaching in Indonesia, September 2016, near Tangerang. On

my left, dojo-cho Zainal Riffandi Anwari.

Before

our panel at Miles Kessler Sensei’s Aikido

at the Leading Edge Tele-Summit (May

15th, 2017 - Panel Discussion: “Old School vs. New School:

Learning Methods In Aikido” | Josh Gold, Charles Colten, Fred

Phillips, moderated by Paul Linden Sensei), Paul Linden sent

interview-type questions to the panelists. The actual panel

discussion took a direction different from those questions, so I

post my original answers here.

What

is your background?

I’m

American. I began my aikido training in Texas in 1973, after a

bone-breaking year in judo. My aikido teachers were Bill Lee,

Rod Kobayashi, Koichi Tohei (in Japan in the mid ‘70s), and

Fumio Toyoda. The latter two emphasized meditation and Zen as

integral to aikido. I’ve been a traveler since Toyoda’s death in

2001, living in 4 countries and visiting and teaching in dojos

in a couple dozen, in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and the

Middle East. I’ve seen a huge variety of practice styles and

technical emphases. Toyoda wanted his students to absorb diverse

inputs. I think I’ve followed his advice in spades.

What

is the old model of learning aikido?

The

teacher demonstrates. The students vigorously practice what they

think they saw the teacher doing.

What

are its drawbacks?

Students

practice technique incorrectly, and pass the errors on to their

students.

What

are its benefits?

Good

aerobic exercise. Trial-and-error learning, if ukes offer more

encouragement than correction for beginner nages, helpfully show

more advanced students where a wrong execution can be blocked,

and strive for vigorous realism with yudansha.

What

is the relation between teaching and learning in aikido?

Same

as for any subject: Teaching helps you learn. A teacher has to

decide what is important to convey, and codify it for

transmission. Dojo duty differs from academic subjects though,

in that it includes the sempai-kohai relationship; everyone is

responsible for teaching.

I

recall a small woman trying to execute kokyu nage on a very big

guy. She could not move him. After several tries, she reached up

on tiptoe and kissed his cheek. He was so unnerved, he fell

down. The student found a new way to lead the partner’s mind,

and I learned from the student that there are many creative ways

of leading.

What

new approaches have you seen being used?

Tohei

Sensei knew he couldn’t make short-term visitors to Japan into

expert aikidoists. He emphasized teaching visitors how to

conduct aikido classes, and how to re-create technique through

reference to his ki principles – what Paul Linden Sensei has

called “teaching algorithms, not technique.” Toyoda’s

organization is focused on developing high teaching standards.

Today a lot of aikido is being taught, but we still don’t see

much teaching how to teach. It is needed.

More

recently, YouTube is fantastically valuable. This week Mr.

Kessler is showing us the value of social media in teaching

aikido – or at least in talking about aikido! Teachers do talk

more these days, sometimes too much. In my early years, the only

words teachers said to me were, Try Again!

YouTube

of course is only visual learning, without feedback. New

Internet devices are appearing that allow fuller tactile and

proprioceptive interfaces. I’m sure these will be marketed first

as sex toys, but soon someone will figure out how to transmit a

good katate tori.

What

approach do you use? Can you briefly summarize?

First,

I like humor as a teaching tool. When people laugh, their

breathing improves, and the lesson is better retained. I have to

be careful in the various countries, when I’m “joking

seriously,” to avoid cultural gaffes and translation problems.

Also I limit it so that students who are worried about their

performance, or just taking themselves way too

seriously – as opposed to correctly taking the martial art

seriously – will not think I’m making fun of them.

Second,

I motivate students by getting them to experience something

outside their everyday reality. As a beginner I had read about

aikido’s unusual mind-body effects, and I’d found ideas like the

unbendable arm implausible. My earliest teacher, Jay Portnow,

never mentioned ki, but one day he made us do the shomen uchi

ikkyo exercise ad nauseum: 1, 2! 1, 2! 1! And he heaved on my

arm, and nothing

happened. My arm didn’t bend. It was a “Wow, man” moment.

Last year in Indonesia, students asked about “no-touch throws.”

They were skeptical. But because these throws are just a matter

of timing and posture, and no deep mysteries are involved, they

were all performing them well within 20 minutes.

I

most enjoy students who are open to being shaken out of their

preconceived reality.

Sometimes

motivation is just a matter of cutting in to a pair practice, to

move an uke who is stymying his nage by standing solidly, and to

move him without using effort, without conveying any tense or

fighting signals. When that student has been trying for ten

minutes to move his even bigger partner, that kind of teaching

makes a lasting impression.

How

do you convey it?

Listen,

I am in no way the world’s hottest aikidoist. Flashy

demonstrations are out of the question. But I am a very good

teacher, and I focus on diagnostics. Rather than just show right

and wrong ways of doing a technique, I see where each student’s

movement needs adjustment, and show them, go this way, not that

way. The next student needs something different.

What

are the benefits of the new approach?

It

must be working. When I move on to a new job in a new country,

my students have actually got angry with me for leaving.

What

areas do you focus on?

That

aikido is martial art. Spiritual development comes from dealing

with the prospect of your own eventual death, a prospect that

logically can’t be separated from the idea of martial art.

That

meditation, whether Zazen or some other form of it, helps you

with that philosophical question, helps you understand your body

and your mind, and increases your flexibility in meeting the

unexpected, on the mat or off of it.

In

my day job I’m a management professor. Fifteen years ago I wrote

a book bringing my two lives together. It’s called The Conscious Manager: Zen

for Decision Makers. Miles has given copies to some of

you. Readers find it “difficult but rewarding,” ha ha. Though

it’s only peripherally about aikido, it is in the spirit of

Tohei Sensei’s “Aikido in Daily Life.”

What

areas do you not attend to?

Here

I should say that a beginning teacher’s most common error, aside

from talking too much, is showing too many wrong ways to do a

technique. By the time a teacher has shown the class six “most

common errors in this technique,” the class has forgotten the

right way to do it! I emphasize this for beginning teachers.

Students know that demonstrating wrong ways is easier than

showing the right way. You will lose credibility if you do it

too much.

Let

the students make the mistakes on their own – even if it’s the

same mistake many generations of students have made before. Body

learning is more powerful than visual learning.

I

don’t see any Japanese instructors in this tele-summit! I

believe most of them would be horrified that we’re here talking

talking talking.

Is it

different for different individuals?

Absolutely.

There are four or five ways to successfully execute each

technique, but hundreds of reasons for students to believe they

cannot do it. The

reasons come from all the “domains” Paul has listed

(intellectual, physical, emotional, social, international,

ecological, and spiritual). “I’m not strong enough.” “I’m too

tense.” Or all too often, “I’m just a girl.” Yes really, we’re

still hearing that last one, at least in Asia, in 2017!

Obviously

not all these reasons are easily visible. The teacher must

discern what is bothering each student, and suggest how the

student may work it out.

My

absolutely most memorable experience as a teacher involved a

Vietnam veteran who had been a tunnel rat during the war there.

Now, this was the scariest possible duty; underground, you could

never know what weapon or booby trap would await you around the

next corner. Before the seminar, his teacher warned me that this

fellow had been a continuous nervous wreck through all the 15

years following the end of the war. He was muscling and

twitching his way through a technique. I showed him how to

effect the technique with no effort. The look that came over his

face showed his epiphany. It said, “I don’t have to struggle

after all.” He started crying. He sat on a bench for a while,

then rejoined the class, with a completely different body

posture.

Who

is your intended audience?

Anyone

who sincerely wants to learn.

Do

the tools you teach work across cultures?

They

need customization. Koreans tend not to stand close enough to

their attackers following the initial tai sabaki. This is

because the customary interpersonal distance in Korea is farther

than, for example, in the USA. In Korean aikido and tango

classes, we have to insert a “hugging practice” module. This

kind of thing is no problem, on the other hand, in for example,

Egypt, where very close conversational distance is the norm.

O-Sensei

called aikido a universal art. Toyoda Sensei thought aikido was

inseparable from Japanese culture. We could have a very

interesting chat about that. Tohei Sensei complained that his

Japanese students trained hard physically without thinking about

aikido, and his American students thought about it, said “I got

it,” and then didn’t want to train. He joked that maybe Hawaiian

students would show the right balance.

Do

they give everyone much the same results?

In

the kyu ranks, yes, because we want standard performances on

promotion tests. For dan ranks, we want to see technique infused

with the student’s personality. We want to see they’ve made the

art of aikido their own while they’ve developed technical skill.

I

am okay with today’s talking talking talking, because though

we’re all traveling the same path, we all find our own

obstacles, and frequently find ourselves on what George Leonard

Sensei called plateaus of learning. That is, we advance not with

smooth continuity, but in fits and starts. We need to hear the

same truth repeated using different voices and vocabularies –

the vocabularies of the faculty of this tele-summit – to get us

off the current plateau and on to the next.